Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” That’s a simple, profound and true statement.

Moynihan’s words have particular relevance for our country and society after Donald Trump’s shocking 2024 election victory. To put things directly, Trump was able to win because he and his followers convinced most of the country to believe in his falsification of factual truth.

Factual truth is distinct from ideology or bias or personal opinions of any kind. Rather, for example, the factual truth is that my name is Robert Jay Lifton, I am a research psychiatrist who studies the psychological roots of war and political violence, and I am writing an article for Scientific American. This is a declarative sentence that makes an irrefutable point. That irrefutability is the source of the appeal of factual truth.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In contrast, when factual truth breaks down—with a denial, say, of the outcome of a legitimate election—there can be a rush of factual falsehoods inundating a whole society. That is because factual untruth requires continuous additional untruths to cover over and sustain the original one. And the defense of continuous falsehoods relies on more than repetition; it relies on intimidation and can readily lead to violence. Philip Roth had both the falsehood and the violence in mind when he spoke of the “indigenous American berserk.”

What results from this situation is malignant normality, society’s routinization of falsehood and destructive behavior. That can produce psychic numbing, the inability or disinclination to feel, which can reach the point of immobilization.

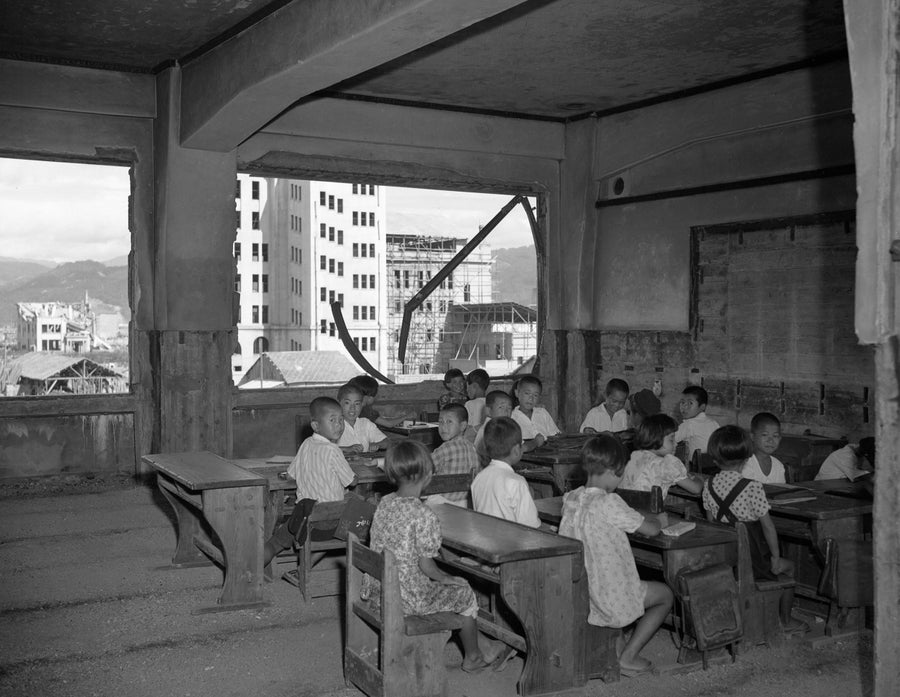

Children in Hiroshima one year after the bomb.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Malignant normality has much overlap with the term “sanewashing.” That term does connect with a wider audience but can become glib and vague. Malignant normality, in contrast, has a greater suggestion of a psychological experience on the part of individuals and groups.

Given how widespread falsehoods and lying have become, any reference to the value of truth telling can seem counterintuitive. But factual truth telling can bring psychological relief to the teller who can disengage from malignant falsehoods. In this way, truth-telling helps diminish psychic numbing.

I have also emphasized in my work how much we human beings are meaning-hungry creatures. That is radically true for survivors of war, nuclear or conventional, or other extreme trauma. For any such meaning to be convincing it must be based in factual truth.

It is wrong and misleading to speak of us as a “post-truth” society. Rather, we are a society that is continuously engaged in a struggle for truth telling, which can be a profoundly difficult enterprise, as the 2024 U.S. elections made all too clear.

To cope with the catastrophe of a second Trump administration and counter the serial lying, we require every imaginable means of truth-telling. And the truth-telling itself becomes an expression of activist resistance.

In each of my research studies, I have sought to bear witness to the truths I encountered. The principle of truth telling was central to all of my work. In Hiroshima, for instance, my work took the form of a scientific interview study of hibakusha, the survivors of the atomic bomb. But I found it necessary to add the broader ethical commitment to tell the story of the bomb’s annihilative human impact. In that way I had to become a witnessing professional, which meant not only revealing the full Hiroshima catastrophe but combatting the nuclearism that led to it, the embrace of these weapons to solve human problems and the willingness to use them.

Truth was at the heart of my study of antiwar Vietnam veterans and their antiwar movement. The veterans I interviewed came to find their meaning of the war in its meaninglessness. Indeed, Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) affirmed that meaninglessness as well as their committed effort to oppose their own war.

Hannah Arendt, the renowned philosopher known for her study of totalitarianism, noted that it relied on “the organized lying of groups.” She pointed out that leaders like Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels promoted what they themselves called the “big lie,” not only to suppress their people but to control their sense of reality. In that way Nazi leaders could seek the ownership of reality by achieving widespread national belief in falsehood. There is a sense in which all of Germany became a mystical cult with Hitler its guru and savior. Truth-telling was also at the center of my own study of the murderous behavior of Nazi doctors.

There is a certain cultlike parallel in Trump’s claim to omniscience, believed in by his hardcore followers, and his continuous claims of the ownership of reality.

Although they lost the election, Kamala Harris and Tim Walz touched a national nerve when they began using the word “weird” to describe Trump and his running mate J.D. Vance. This was because it brought us collectively back to a democracy that functions on factual truth. A weird person is one you should never follow because if you do, you take on some of that weirdness, the loss of reality and overall obliviousness to factual truth. That becomes very dangerous to a society facing planetary threats such as nuclear war and global warming. Weirdness threatens our security, individually and nationally. But rather than avoidance, the election sustained and extended our dangerous participation in weirdness.

In sharp contrast to the serial falsehoods of Trump and Vance, the Harris-Walz team sought to be truth-telling throughout the election process and constantly called out those lies. To be sure, Harris and Walz could exaggerate claims, leave out uncomfortable changes that each underwent in their advocacies, and avoided difficult topics. But they talked about factual matters and factual possibilities.

The election was an ultimate test of the amount of factual truth our society could manage. Not enough, it turned out. But even with the election defeat, our society still hungers for those factual truths.

Trumpists are likely to continue their creation of atrocity-producing situations, whether having to do with “ungoverning,” climate, threatened violence, or harmful policies around the lingering planetary threat of COVID. But we are not helpless before them.

In response to my study of Nazi doctors, some friends would ask me “Now what do you think of your fellow human beings?” They were expecting me to say, “Not very much.” But my answer was that we could go either way. We could perish from our catastrophes or survive them by making use of our “better angels” (in Lincoln’s words) that provide us with sufficient survivor wisdom to keep our species going.

We are not condemned by a death drive to destroy ourselves; nor is it certain that we will sustain a truth-centered, life-enhancing ethos. But we have the capacity for that ethos, which provides a strong source of hope.

The award of the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize to the hibakusha group Nihon Hidankyo for its antinuclear activism is a powerful assertion of such hope. So was Harris’ insistence that, though she conceded the election, she would never give up struggle “for freedom, for opportunity, for fairness and the dignity of all people.”

We cannot expect that we will eliminate falsehood entirely. There is no absolute moment of realized factual truth. Rather we are engaged in a continual struggle, as individual people and as a country, on behalf of the decency, necessity and satisfaction of truth-telling.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.