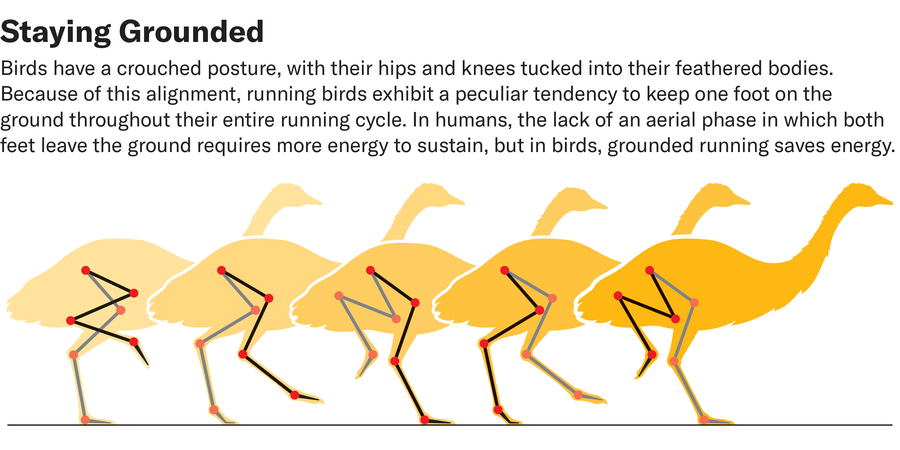

When humans want to move fast—barring speed-walking races—we pick up our feet. But when birds need to get somewhere quickly without flying, they tend to always keep one foot on the ground, leading to a strange-looking gait that scientists call “grounded running.”

“Most people won’t even probably realize that they’ve seen a bird use grounded running,” says Pasha van Bijlert, an evolutionary biomechanics graduate student at Utrecht University and Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands. “Some of the times that you see a bird walking in a weird way, they’re actually not walking; they’re running—you can tell from the fact that they’re bouncing.”

Grounded running in birds has puzzled scientists because humans mimicking the behavior use quite a bit more energy to achieve a running pace than we do with our habitual rapid movement style, called aerial running. But research by van Bijlert and his colleagues in Science Advances finds that birds aren’t foolish for using grounded running—even though they may look silly.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A virtual model of an emu used to study bird locomotion.

Pasha van Bijlert

For the study, the scientists used a computer model of a Common Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) to show that the bird’s posture makes grounded running more efficient than aerial running at certain speeds. Researchers built the model because they expected two factors to influence the birds’ movement: their highly elastic leg tendons and their crouched stance, with hips and knees tucked into their feathered body.

Neither factor lends itself to physical experiments. “You can’t really change a bird’s anatomy and see how that affects its running styles,” van Bijlert says. “I can’t train an emu to stand up straight.” Hence the simulation approach, which allowed the researchers to adjust emus’ leg anatomy and prevent the tendons from storing energy as they tested what gaits were most efficient for moving at certain speeds.

The simulation alone is impressive work, says Armita R. Manafzadeh, a biomechanist at Yale University, who was not involved in the new research. “Physics-based simulations with locomotion has come such a long way,” she says. “When this kind of methodology first started out, there were so many simplifications being made and the algorithms were so simplistic that the outputs on the computer really didn’t look like a living animal at all.”

Brown Bird Design

The simulations showed two strategies for reducing energy expenditure during faster movement: either keeping legs relatively straight during the running cycle or keeping one foot on the ground as much as possible. Humans take the first route, but birds can’t—so they use grounded running instead. (Humans asked to run in a crouched position will instinctively switch to grounded running as well; give it a try if you’re interested.)

“If we think about bird locomotion through a human lens, then [grounded running] seems like a really weird and kind of dumb thing to do because it seems really energetically costly,” Manafzadeh says. “It’s actually a pretty smart thing to do when you have the anatomy of a bird.”

Van Bijlert says the research may also inform scientists’ understanding of birds’ long-lost ancestors: dinosaurs. He suspects that especially dinosaurs that are closer relatives of birds, such as the petite velociraptors, might have chased down their prey like nightmare agents of the Ministry of Silly Walks. But more simulations are needed to determine whether bipedal dinosaurs, including the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex, also might have practiced grounded running, Manafzadeh says. She adds that she hopes the new research reminds scientists to be curious about how other species experience life on Earth. “If we try to interpret the diversity of animal locomotion through a human-centric lens,” she says, “we’re going to miss out on lots of really cool and equally viable ways of moving around the world.”

A version of this article entitled “Goofy Running” was adapted for inclusion in the December 2024 issue of Scientific American. This text reflects that version, with the addition of some material that was abridged for print.