In 2014 astronomers announced a whopper of a discovery: primordial waves from the earliest moments of the big bang. The South Pole telescope results validated the long-standing but still-shaky hypothesis of cosmic inflation, the scenario where the extremely early universe underwent a period of massively accelerated expansion. News reports went wild, as did the scientists involved in the study, in a celebratory news conference.

But it was all just a bunch of dust. Literally, dust. The team did not properly account for the impact of interstellar dust in their analysis. With proper calibration, the paradigm-shifting result disappeared.

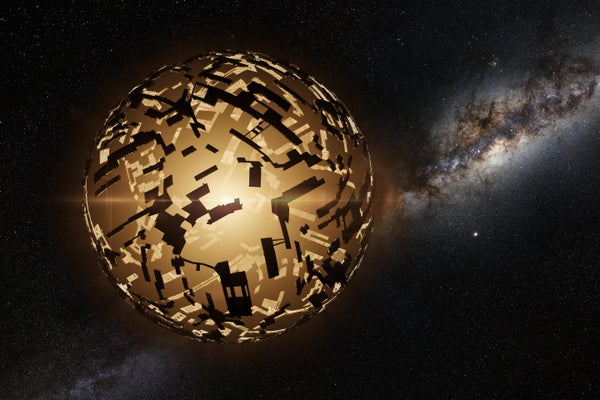

Or remember Tabby’s Star? In 2015 astronomers speculated that its strange light pattern might be the product of alien megastructures. Cue media circus, high-profile talks, the works. Further analysis revealed that it was ... dust, again.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

More recently, a group of astronomers claimed to find phosphine in abundance in the Venusian atmosphere, proposing that there might be some form of exotic life floating in the cloud tops. After the media hype died down, other researchers found significant flaws in the original analysis (at least it wasn’t dust this time).

It’s not just astronomy. Neutrinos can travel faster than light. Mozart makes your kids smarter. Dyeing your hair gives you cancer. Smartphones make us stupid.

Very, very stunning. But very, very wrong.

The strong correlation between flashiness and wrongness comes from several factors. First, much, if not most, scientific research is wrong. That’s why it’s research; if we knew the answers ahead of time, we wouldn’t need to do science. Many scientific papers are speculative, dependent on hyperspecific assumptions of controlled parameters, or just crazy ideas shot into the dark. It’s through this constant bubbling of ideas and results and studies that we poke and prod at nature’s workings, hoping to tease out some glimmer of deeper understanding.

Second, scientists endure perverse incentives to publish as much as possible—to “publish or perish”—and to get their results in top-tier journals as much as possible. Since the biggest ones only take on the most impactful research, there is tremendous pressure in academia to inflate results and make big, bold claims, increasing the chances that their tenuous results will not hold up to further scrutiny.

Lastly, there’s the modern-day hype machine. While many journalists respect scientists and want to faithfully represent the results of scientific research, publishers face their own incentives to capture eyeballs and clicks and downloads. The more sensational the story, the better.

Trust in science continues to decline, reports the Pew Research Center, falling to only 57 percent of survey respondents viewing it as more positive than negative for society. I believe that’s in part due to flagrant overinflation of scientific results. The more times that the public sees science contradict itself, the less likely people are to believe the next result that makes headlines. And the more times that scientists are loudly, publicly wrong, the more ammunition antiscience groups have in their fight against trusted experts.

It’s not to say that science results can’t be both interesting and right. The discovery of gravitational waves from merging black holes in 2015 was supremely fascinating, and exactly right. The release of the mRNA vaccines to fight the coronavirus pandemic were nothing short of miraculous—and they did the job.

The vast majority of the time, though, from my experience in the worlds of science and science communication, if a result is interesting, it’s probably wrong. And let me be clear here. I’m sure you find most, if not all, scientific research absolutely fascinating—as do I. But the more interesting a result is to the wider community, with more headlines, chatter, attention and raised eyebrows, the more likely it is to be worthy of a bit of healthy skepticism.

Just peruse the latest batch of articles from your favorite science journal. Once you get past the technical jargon, you’ll find that many papers are, in a way, boring. Not boring in the sense of not worth reading or exploring further, but boring in the sense that they would not make the pages of a high-impact journal, let alone your local newspaper. Most scientific papers are small steps, methodological techniques or slightly-off-the-beaten-path theoretical detours. Most scientific results come slowly, incrementally and with little fanfare.

Only a slim fraction of science results makes it from the journals to the newspapers, and even fewer make global headlines. The broad public only gets to view science through a highly filtered lens, and what makes it through that filter has a greater chance of being wrong.

The best approach to take with science results, news, and headlines is the same approach scientists use themselves: healthy skepticism.

First, look at the timeline. Amazing results can be right, but they’re usually backed by years, if not decades, of consistent, steady progress in those directions. It took a quarter century of effort before gravitational waves were found, and the roots of the mRNA vaccines go back to the 1990s. A big, successful result is usually the final step of a slow and steady slog.

Second, look at the scope. Bigger claims, with more far-reaching or broad conclusions, usually don’t hold up. Good individual studies usually have carefully crafted limitations and clearly stated caveats; it takes a comprehensive effort from a community of scientists to build up a general consensus. Climate change proved true over time, black holes were a fringe possibility that added up in repeated observations, and exoplanets were searched for over decades before the first one was finally spotted in 1992.

Lastly, just be patient. Science is in part organized skepticism, and the first group of people to rigorously attack a new idea will be other scientists. New studies may rebuke, reaffirm or revise an existing result. Only time, and countless hours of work, will reveal if a conclusion holds up to scrutiny and the ultimate judgment of evidence.

Beware big headlines; don’t believe everything you see. But when study after study comes out, building up an interconnected latticework of theory and experiment, allow your beliefs to shift, because that’s when the process of science has likely led to an interesting and useful conclusion. It’s ironically through this process of healthy skepticism that trust in science can be regained. By viewing science results through a scientific lens—initially skeptical but allowing beliefs to shift along with the weight of evidence—we can develop the intuition we need to reject sensational headlines but know when a new result is right.

In the meantime, just remember that if it’s interesting, it’s probably wrong.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.