Most scientists can never receive a Nobel Prize, arguably the most prestigious award in science. Only physicists, chemists, and specialists in physiology or medicine are eligible for the honor—which comes with a gold medal, a diploma and currently up to 11 million Swedish kronor (about $1.07 million).

Multimillionaire Alfred Nobel established the prize pot—and those categories—in 1895 via his last will and testament. He decreed:

[My capital] is to constitute a fund, the interest on which is to be distributed annually as prizes to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The interest is to be divided into five equal parts and distributed as follows: one part to the person who made the most important discovery or invention in the field of physics; one part to the person who made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who, in the field of literature, produced the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction; and one part to the person who has done the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That seems straightforward. The first awards in the science categories were presented in 1901 to Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (physics), Jacobus H. van ’t Hoff (chemistry) and Emil von Behring (physiology or medicine).

But the inaugural prizes in chemistry and physics honored work that traced further back in time than “during the preceding year”—one was connected to research that started in the 1870s and the other to research from 1895. Indeed, Scientific American calculated that between 1901 and 2023, the time between key research dates and a Nobel nod averaged 20 years across categories. And in 1902 joint winners began popping up, with Hendrik A. Lorentz and Pieter Zeeman sharing the physics prize for their work on magnetism and radiation.

That broadening of the award eligibility from Nobel’s will is thanks to statutes instituted by the Nobel Foundation and his heirs in 1898. Specifically:

The provision in the will that the annual award of prizes shall be intended for works ‘during the preceding year’ should be understood in the sense that the awards shall be made for the most recent achievements in the fields of culture referred to in the will and for older works only if their significance has not become apparent until recently....

A prize amount may be equally divided between two works, each of which is considered to merit a prize. If a work that is being rewarded has been produced by two or three persons, the prize shall be awarded to them jointly. In no case may a prize amount be divided between more than three persons.

The timing statute is relatively clear. Simply put, award-worthy research doesn’t have to be limited to the year preceding the award. But the joint winner statute is more complicated. What does it mean?

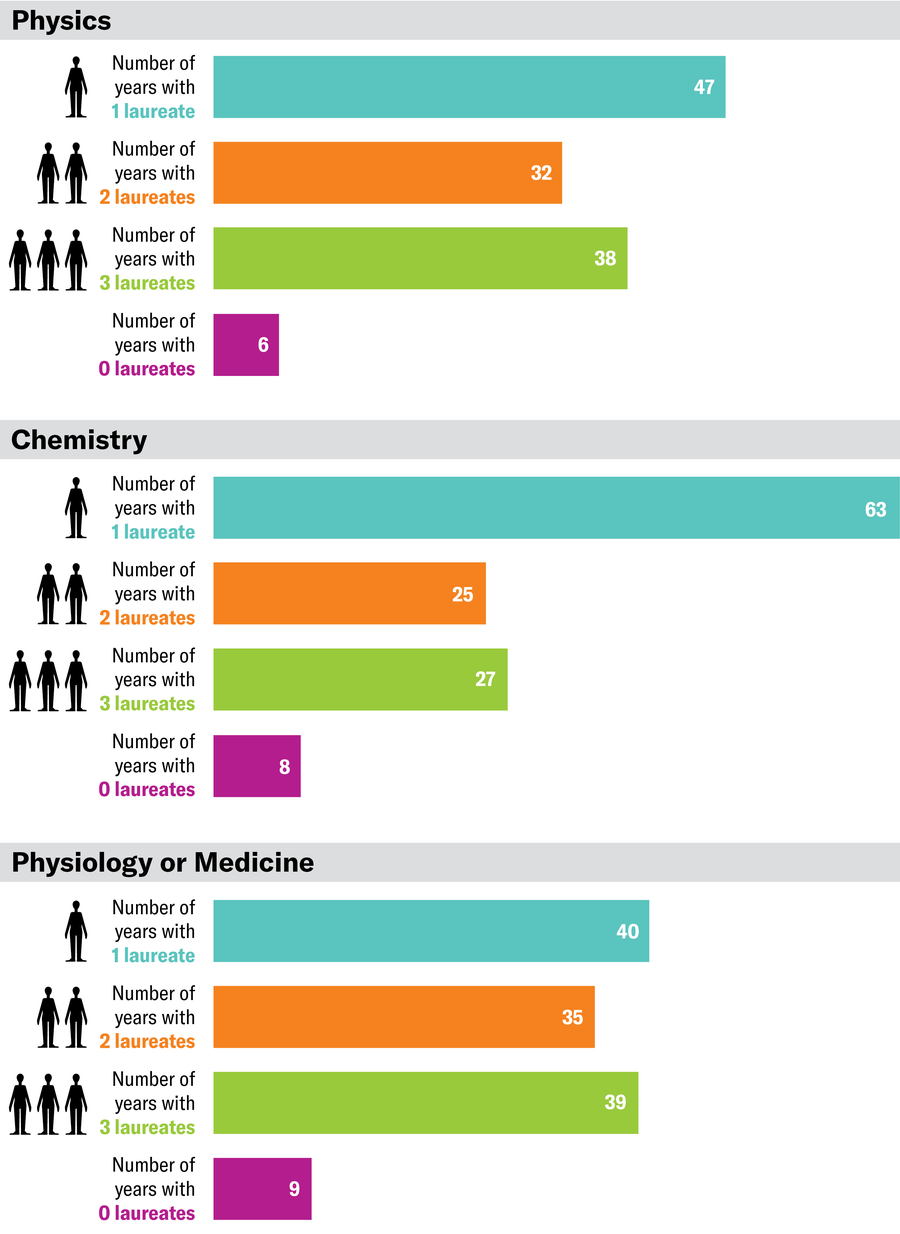

For the science categories of physics, chemistry and physiology or medicine, up to three recipients—also known as laureates—can be awarded in any given year. Here’s the breakdown from 1901 through 2023.

Jen Christiansen

But joint laureates aren’t always direct collaborators. For example, James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo were awarded the 2018 prize in physiology or medicine for their research on proteins that inhibit our immune system and the way those proteins could be manipulated to fight cancer. Both contributed crucial findings to the emerging field of cancer immunotherapy, but they worked in parallel—in different labs with a focus on different mechanisms.

Many joint laureates aren’t even contemporaries. For example, the 1986 prize in physics went to Ernst Ruska, Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer to celebrate work completed 48 years apart. Ruska developed the first electron microscope in 1933, and Binnig and Rohrer developed the scanning tunneling microscope together in 1981.

And although each recipient is awarded their own personalized gold medal and diploma, the prize pot of money isn’t necessarily evenly distributed amongst joint laureates. This can all get a little confusing—unless you shift focus from the people conducting the research to the work being celebrated.

Per the statute, “A prize amount may be equally divided between two works, each of which is considered to merit a prize.” Note the emphasis on “works.” At its core, the research is being celebrated, not the researcher. Further, the statute says that “if a work that is being rewarded has been produced by two or three persons, the prize shall be awarded to them jointly. In no case may a prize amount be divided between more than three persons.”

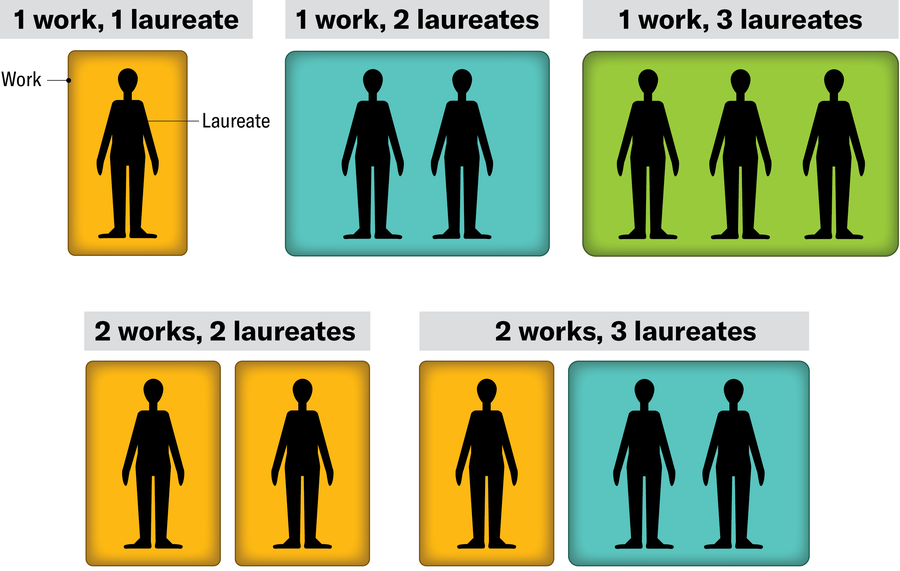

Overall, there are five possible scenarios:

Jen Christiansen

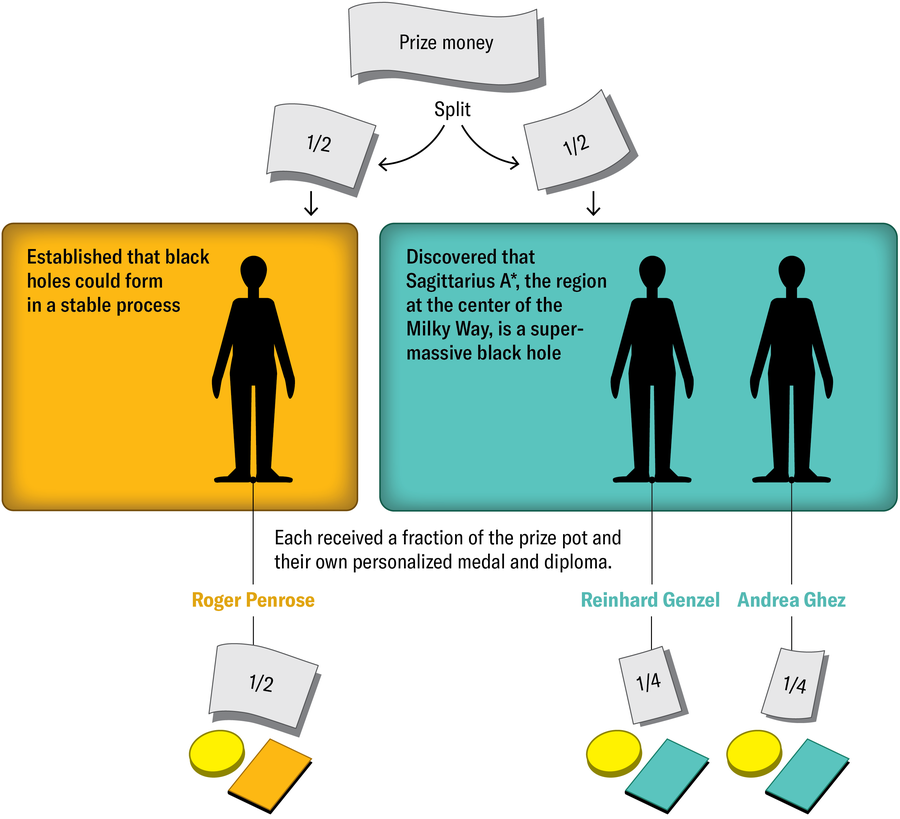

Here’s how it played out in 2020. The prize in physics was awarded to Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez. Penrose was celebrated, as the Nobel Foundation states, “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity,” a contribution pinned largely to an article published in 1965 in which he established the physical foundations of black holes. Genzel and Ghez were both celebrated “for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy”—work done some 25 years later in parallel, with separate teams.

One half of the prize money was awarded to Penrose, and the other half was split between Genzel and Ghez.

Jen Christiansen

Interestingly, the statute doesn’t strictly follow the language in Nobel’s will. He centered the influential “person,” not the “work.” Even now, almost 123 years after the first ceremony, that tension doesn’t feel resolved. The awards committee calls out and popularizes up to three people each year in each category and hands each of those scientists a check. Yet the awards are pinned to works, in a world in which the work being recognized is increasingly the result of many collaborators. This conflation of headlining scientist and work done by many is at the heart of many Nobel Prize critiques (although there are also other facets worthy of criticism, including a stunning and problematic lack of diversity among the laureates).

As Caroline Wagner, a scholar of science and technology with a focus on international collaboration, wrote in 2017:

While practitioners have expanded the way contributions are credited, awards like the Nobel Prizes haven’t caught up. The little bit of science history taught in school still focuses on individual contributors such as Marie Curie and Albert Einstein. Harder to explain or visualize are the cross-disciplinary collaborations that constitute most of science today.... The Nobel Prize, developed to recognize 19th-century creativity, may no longer reflect the true contributions within 21st-century science.

And yet many people—myself included—are still charmed by the thought of a scientist getting caught off guard by that Nobel announcement phone call and having their routine day transformed into a spectacular one. And there’s something lovely about the science communication flurry that follows, providing us all an excuse to revisit impactful research together.